Sleep

How Friends Buffer the Link Between Bullying and Sleep Problems

Having close friends in their corner could help children who are bullied.

Posted November 15, 2022 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Children who are bullied experience a number of negative emotional and physical consequences, often including poor sleep.

- Recent research finds that having at least one close friend could help protect bullied children from sleep difficulties.

- The more friends a teen reported having, the less impacted their sleep was by peer victimization.

- Promoting the importance of close friendships could help improve the lives of children, especially those who are victimized by peers.

Peer victimization refers to a wide range of negative experiences that children and adolescents are subjected to at the hands of their peers, often in the school setting. Peer victimization can include being a target for teasing, false rumors, verbal threats, or even experiencing physical violence.

A number of studies have shown that up to 15 percent of young people report being consistently victimized by their peers. Accordingly, the causes and consequences of peer victimization are of serious concern to school administrators, teachers, parents, and children/adolescents alike.

Moreover, the consequences of peer victimization are widespread. Those who report being victimized by their peers are also more likely to feel lonely and rejected and to have lower self-esteem. They are also at higher risk of exhibiting symptoms of anxiety and depression. Not surprisingly, peer victimization is also linked with less enjoyment in school and poorer academic performance. In some cases, the repercussions of peer victimization have even been shown to predict lower earnings years later, well into adulthood.

Some of the effects of peer victimization also manifest in somatic complaints. For example, those victimized as youth report feeling more fatigue, loss of appetite, dizziness, and generalized physical pain. And one key area in which children and adolescents may be impacted by peer victimization is their sleep.

Adolescence is already a period of transition in sleep patterns. “Delayed sleep phase preference” means that adolescents tend to prefer going to sleep and waking up later than they did as children. In conflict with that, most adolescents are expected to be up and ready for school early than their changing sleep cycles accommodate. As such, understanding the factors that impact adolescents’ sleep quality is particularly relevant.

How Peer Victimization Affects Sleep

In a recently published study in the Journal of Genetic Psychology, my co-authors and I examined data from a large sample of Brazilian adolescents to better understand how reports of victimization by peers were related to sleep difficulties.

In 2012, the Brazilian government organized a nationwide cross-sectional study of adolescent health (the National Survey of School Health through the “Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatıstica”). Young people between the ages of 11 and 19, from public and private schools across all 27 Brazilian states were recruited. Over 100,000 young people participated in this study. In doing so, they reported their experiences of peer victimization over the last 30 days and the number of sleep difficulties they experienced in the last year.

Thankfully, most of the youth were rarely victimized, but those that were reported more sleep difficulties. The most interesting detail, however, was that this effect was significantly less pronounced for youth who reported having a close friend. In other words, the detrimental impact of peer victimization on sleep difficulties appeared to be buffered among adolescents who had more close friends.

In the area of peer relations, there have been several studies exploring the buffering role of friendships for children and adolescents. Not only are young people less likely to be victimized if they have at least one close friend, but even when they are, we don’t see the same negative outcomes.

For example, in a previous study of ours, we were able to show that negative peer experiences were related to lower self-esteem and higher secretion of cortisol, a hormone that is a key component of our body’s “fight or flight” response. This effect completely disappeared, however, if children reported having their best friend with them at that moment.

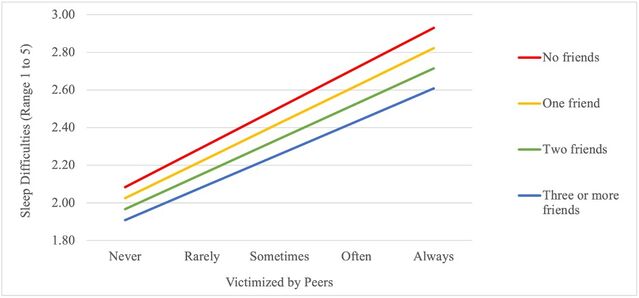

In the current study, adolescents reported whether they had no close friends, at least one, two, or three or more. Just like in other studies, having more friends was related to less victimization overall. More importantly, though, was that the number of friends changed the association between peer victimization and sleep difficulties. As the figure below illustrates, the more friends a teen reported having, the less impacted their sleep was by peer victimization.

Figure of the association between how often an adolescent was victimized by their peers and reported sleep difficulties as a function of number of friends.

It’s worth noting that we also found gender differences in these effects. The biggest gender difference was that girls reported more sleep problems overall. In addition to that, the buffering effect of having more friends benefited boys more than it did girls. In other words, girls who reported being victimized also reported more sleep difficulties, regardless of how many friends they had.

What We Still Don’t Know

As revealing as these findings are, there’s a lot we still don’t know. For example, why is sleep among boys who have friends less impacted by peer victimization compared to girls? Perhaps more compelling, what processes explain why having close friends helps immunize adolescents to the effects of peer victimization on sleep?

Past research offers some hints. For example, friended children and adolescents are less likely to blame themselves in response to being victimized. If victimized, they are also less likely to engage in rumination (i.e.: dwelling on their negative thoughts). The cognitive benefits of being friended might translate to better sleep. We aim to find out.

For us, our goal is to continue to highlight the measurable benefits of friendships for children and adolescents. Although a number of researchers, including ourselves, hope to capitalize on various ways to reduce victimization in schools, until we do, promoting the importance of close friendships as a means to mitigate its effects is another avenue towards improving the lives of young people. Then, maybe, we can all rest easy.